Everyday dairy products such as butter, yoghurt and cheese could become luxury items in Britain after Brexit, with price rises being caused by the slightest delay in the journey from farm to table, a report by the London School of Economics finds.

The LSE research, commissioned by the company behind Lurpak, Anchor and Arla brands, also found that speciality cheeses could become scarce after Brexit, with escalating costs whatever the outcome of the exit negotiations.

Ash Amirahmadi, the UK managing director of Arla Foods, said: “Our dependence on imported dairy products means that disruption to the supply chain will have a big impact. Most likely we would see shortages of products and a sharp rise in prices, turning everyday staples like butter, yoghurts, cheese and infant formula, into occasional luxuries. Speciality cheeses, where there are currently limited options for production, may become very scarce.”

The LSE report comes a year to the day after the government was warned that it was “sleepwalking” into a post-Brexit future of insecure, unsafe and increasingly expensive food supplies.

Britain’s food production deficit has been put in the spotlight after repeated warnings that the country needs to rely less on imports to feed the population.

Britain does not produce enough milk to keep up with demand, creating a dependency on the EU, including on dairy-surplus countries such as Ireland, Germany, France, Belgium and Denmark for everyday items such as cheddar cheese and butter.

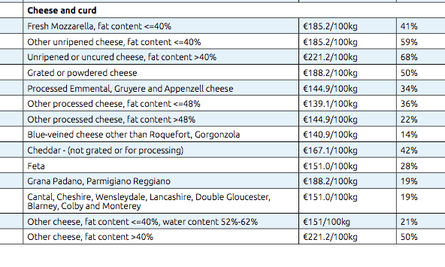

If the UK crashes out of the EU with no deal and defaults to World Trading Organisation rules, prices will almost certainly rise as dairy products, along with meat, attract high tariffs.

A milk product with a fat content of 3% to 6% has a tariff of 74%, while fresh mozzarella is rated at 41% and unripened cheese at 68%.

Even if a deal were struck and there were no tariffs, imports would face costly delays at Dover, the report says. LSE estimates that every seven-minute delay at a port such as Dover will add a minimum of £111 extra per container because of extra labour costs.

In addition, rules of origin certificates could add €48 (£45), with veterinary controls costing £50.60 per consignment, the LSE finds.

“Fuel costs, lorry maintenance, loss of perishable goods shelf life and increased wages of lorry divers, mean the above figures [are] at the lower end of the likely range,” finds the LSE.

The research suggested that small cheese suppliers in France and Italy could find their products uncompetitive in British shops, generating scarcities and, in turn, price rises.

Amirahmadi said it was important to be clear that Brexit might bring opportunities to expand the dairy industry in the UK, boosting the country’s declining food security levels. However, he warned that this would take time.

“Brexit might bring opportunities to expand the UK industry in the long-term, but in the short- and medium-term we cannot just switch milk production on and off. Increasing the UK’s milk pool and building the infrastructure for us to be self-sufficient in dairy will take years,” he said.

Arla is the largest dairy company in the country with a turnover of £2.6bn and supplies the big supermarket chains including Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Asda with branded and own-label products. It is a pan-European cooperative with production facilities in 11 countries supplied by its 11,200 dairy farmers, 2,400 of which are British.

Commenting on the LSE report, Amirahmadi suggested that farmers who owned the Arla dairy cooperative already offered the consumer the best possible price.

“There’s no margin to play with here in the value chain,” he said. “Any disruption means that if we don’t get the practicalities of Brexit right we will face a choice between shortages, extra costs that will inevitably have to be passed on to the consumer, or undermining the world-class standards we have worked so hard to achieve.”